|

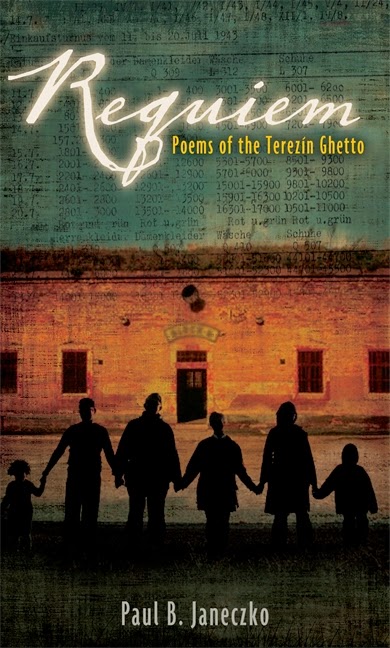

| Cover Image from www.boydsmillpress.com |

Yolen and Dotlich each contributed one poem for "fifteen of the most recognizable fairy tales in Western culture" (Yolen and Dotlich 2013, 5). Some of their poems look at the events of the tale from the point-of-view of different character; some use the same character, but look at the tale through another person's eyes; while still others give a voice to the voiceless or a marginal character. One poem appears on one page and the partner poem on the facing page. They don't list the poet who wrote each particular poem with the title of the poem or on the table of contents. You have to look at the verso title page in order to find out which poems were written by Yolen or Doltich. At the end of the book, Yolen and Dotlich offer additional information about the fairy tales, generally alternate titles of the fifteen fairy tales or alternative versions (different cultures). They also include a few websites where you can find more information: SurLaLune Fairy Tales, Hans Christian Anderson: Fairy Tales and Stories, and Yolen's own website (look under Works).

The fifteen fairy tales Yolen and Dotlich use for inspiration are: Sleeping Beauty, Hansel and Gretel, Beauty and the Beast, The Gingerbread Boy, Cinderella, The Little Mermaid, Jack and the Beanstalk, The Princess and the Pea, Rumplestiltskin, The Frog Prince, Snow White, Little Red Riding Hood, The Three Billy Goats Gruff, Thumbelina, and The Three Bears. Most of them should be familiar to many students, especially those who have paid careful attention to their Disney films or can connect the dots in the Shrek series of films. A couple of the fairy tales -- and I'm thinking particularly of The Frog Prince and The Three Billy Goats Gruff -- might not be as familiar to students as the ones like Cinderella or Beauty and the Beast that have been given the full Disney treatment, i.e. utter ubiquitousness via movie merchandising and membership in the Disney Princess pantheon. Still, this could create an excellent opportunity to introduce students to some of the not-as-well-known fairy tales.

Yolen and Dotlich use a framing strategy to open and close the book. The poem "Once" appears just after the endpapers at the beginning, and "Happily Ever After" closes the book before the endpapers at the end. It's a clever way to begin and end the book, especially because Yolen wrote one of the poems and Dotlich wrote the other. "Once" trots out all the tropes of a typical fairy tale, establishing the foundation of fairy tales in general and the themes of the poems to follow. It says,

A girl, princess, mermaid, widow, witch, queen, wife,"Happily Ever After" asks the readers to consider what happens "after all the plotting, after the ball, / after the spelling, / hopping, / sweeping, / grumping, grousing, mopping, sleeping, / from small glass shoe to nuisance pea (Dotlich 2013, 40). Using those two poems to open and close the device is an elegant use of the device, not only because of their placement outside of the body of the book itself, but because they introduce the concept behind the book and conclude it by inviting readers to imagine the lives of fairy tale characters after the final page is turned. Also, because Dotlich and Yolen each contribute one poem to every fairy tale they feature in the book, it should also follow that they each contribute a poem to the frame around the book.

A boy, king, solider, wizard, troll, giant,

....................................................................................

The tale turns, returns, confesses, confuses,

And all the hardships, spells, and stresses

End well in happy laughter

And we hope --

ever after. (Yolen 2013, 1)

Yolen and Dotlich don't go into much figurative language in their poems here. They do rely on well-chosen adjectives and phrasing in order to convey meaning and emotion. One of the best examples of this is in the two Beauty and the Beast poems, "Beauty's Daydream" and "Beauty and the Beast: An Anniversary." In Dotlich's (2013) "Beauty's Daydream," she repeats certain words and phrases, like 'dream,' or 'dreaming' to emphasize all the wonderful things mentioned in the poem, like dancing, pink flowers in her hair, roses, and valentines only reside in her dreams (12). Dotlich (2013) also repeats the phrase, "If I could" twice to illustrate the longing Beauty feels for her dreams and reality she faces in the Beasts "fangs, his roar" (12). Yolen's "Beauty and the Beast: An Anniversary" is achingly poignant, due to the structure and word choice. In it, an older Beauty narrates her supposedly happily ever after:

My father died last April;By placing just a bit of Beauty's thoughts on each line, Yolen lets them stand alone so the reader has a moment to contemplate how many years have passed (her father's death and sisters' diminished communications) and her, at least to me, well-buried regret at never having children. Yolen also uses language to give Cinderella a rueful tone in "Shoes." Cinderella says, "I could have danced / all night in wooden clogs / or easy-peasy / runners" (Yolen 2013, 16). Yolen uses the poem to mention all the different shoes Cinderella is supposed to have worn in different versions of Cinderella, and highlight how much more suitable they would be for dancing, as opposed to the glass shoes she did wear "that cut [her] feet to slivers" (Yolen 2013, 16). Dotlich also uses the word choice to illustrate the metamorphosis the Little Mermaid underwent in "A Mermaid's Love." The young mermaid changes her "fins to legs / arms to wings" as detailed in the Hans Christian Anderson tale, and Dotlich neatly summarizes the entire story with a few well-chosen words (Dotlich 2013, 19). The quote follows her transformation from mermaid to human to a spirit drifting as foam upon the sea. Dotlich uses short phrasing in "Little Red's Story" to denote the excitement Red feels during her inadvertent adventure when she discovers the Big Bad Wolf at her grandmother's house. Similarly, Yolen's (2013) "About Grandma Wolf" is a short poem, in which the lines "Was I fooled? / Not a bit." carry the smug certainty of a child who knows she was right (31). It's a short, triumphant 'HA!' of a poem.

my sisters no longer write

except at the turnings of the year,

content with their fine houses,

and their grandchildren.

.....................................................

Though sometimes I do wonder

what sounds children

might have made

running across the marble halls (Yolen 2013, 13)

Yolen and Dotlich also use memorable rhythm in their poems. In "Jack," a poem delving into Jack and the Beanstalk, Yolen appropriates two well-known nursery rhymes ("Jack Be Nimble" and "Rock-a-Bye Baby") for the rhythm of the poem. Yolen uses "Jack Be Nimble" for the first stanza to parallel the other Jack's agility in bringing down the beanstalk. The second stanza echoes the line in "Rock-a-Bye Baby" that says "Down will come baby / cradle and all" by describing the giant falling "Bottoms up in a crater, / Thus ending it all" (Yolen 2013, 21). The rhythm of Yolen's "Gruff for Dinner", a poem written from the point-of-view of the troll in The Three Billy Goats Gruff reminds the reader of a man rubbing his hands together in anticipation of a good dinner. The rhythm is so well thought-out, it might make an interesting exercise for a music class to set it to music.

Several poems have a rhyme scheme that draws attention to events, plot points, or a narrator's thought process. in Yolen's (2013) "Gretel Spies the Magic House," the last four lines are written in an alternating rhyme scheme that draws a reader's mental eye from the house to the fence and the realization that things aren't going to end well:

We should have...Dotlich's "A Mermaid's Love" also employs rhyme where the rhyming words are significant to the story and the emotional impact. Dotlich also effectively uses rhyme in "The Pea Episode" (The Princess and the Pea). The stanzas are a series of couplets, but the second line rhymes with the first line of the next stanza. It helps tie events from the previous stanza to the next one. Dotlich also uses a bit of internal rhyme within the individual lines of "Troll Lament" (The Three Billy Goats Gruff). It certainly lends the poem a nice rhythm: "Whoosh! He pushed, / leaving me to shiver in the river. / No snack, no scrap" (Dotlich 2013, 33).

Taken the hint

From the marzipan bricks

And the fence posts made of bone rubble.

But it as only when we saw the witch

That we knew we were in deep, deep trouble. (10)

Both Dotlich and Yolen use a poetry form in order to reflect their subject matter. The two poems about Thumbelina are both short poem formats -- cinquain and haiku. Two short poems for "a bit / Of a proper young lady" (Yolen 2013, 35).

The two poems that highlight The Three Bears use fonts to reflect the different characters: Papa Bear, Mama Bear, Baby Bear, Officer Bruin, and Goldilocks. In Yolen's (2013) "Three Bears, Five Voices," Papa Bear's font is printed in all caps, which mimics irate roaring, while Mama Bear's is an emphatic, but quieter, italic. Baby Bear's smaller font makes the reader hear a younger voice in their head. Goldilocks' font is a loopy, cursive font that perfectly fits Goldilocks' flighty nature. Officer Bruin's plain, no-frills font communicates a tone of calm competence. The same font used for Goldilocks in this poem is also used in Dotlich's "Goldilocks Leaves a Letter Stuck in the Door." The font fits the frivolous nature of Goldilocks, who basically says, 'sorry, not sorry' in her letter, claiming,

I was minding my own business,

napping on the just-right bed,

when suddenly

those three growly ones showed up;

..........................................................

You'd think it was their house. (Dotlich 2013, 37).

In a couple of poems, Dotlich and Yolen also repeat phrases that emphasis the emotional content or reflect the often-conflicting nature of some of the fairy tale plots. In "Just One Pea," Yolen (2013) repeats in the voice of the pea under the mattress, "I miss my dear pod, / My peeps and my peers... / I miss my dear pod, / And my seven green peers" (22). It neatly illustrates the loneliness felt by the solitary pea, hiding under a pile of mattresses. The best use of a refrain is in "Who Told the Lie?" Each stanza ends with the same three lines: "Who told the lie? / 'Not I!' / 'Not I!'" (Yolen 2013, 24). The poem cycles through each character in Rumplestiltskin, in a Rashomon-esque fashion, with each character telling their version of events. In the end, who is telling the truth and who is lying? Yolen doesn't say, and it's up to the reader to decide.

There are poems that will appeal to readers of all ages. Some will appeal to more mature readers, like the Beauty and the Beast poems, but others, like The Princess and the Pea poems will appeal to younger readers. This is a great book to have when you have a wide range of ages that use your library or have students who know a lot about fairy tales or have just received an introduction to them.

The poems are often succinct, wry retellings of the fairy tales or speculative peeks into what happened after the fairy tale ends. In many cases, they may be emotional, but not saccharine-sweet or so sentimental that children or young adult readers will be turned off by the feelings in the poems. Most of the poems are charming reflections of their source material. The one or two that don't quite work are still good, and the reasons they don't quite work are minor, like a slightly abrupt ending. Yolen and Dotlich are skilled poets, and their work here demonstrates this.

Matt Mahurin's illustrations range from surreal to dark and foreboding to luminous. The illustrations cover the two-page spread devoted to both poems. The more emotionally complex poems have muted illustrations that reflect the emotional state of the poems. Some of the more comic or emotionally light poems have illustrations that are bright and airy, keeping with the tone of the poetry. The cover art for the book is fantastic. It's a dark, slightly scary forest, that has different elements from the fairy tales featured in the book scattered among the tree trunks. A glass slipper sits in the middle of a path in the forest, surrounded by scattered candies. It might be fun for students to identify the different fairy tales hinted at in the cover illustrations.

Writing twisted or updated fairy tales has been quite popular. There are tons of novelizations that reexamine fairy tales from Yolen's contribution to the Tor Fairy Tale series, Briar Rose, to Gail Carson Levine's Newbery Honor book Ella Enchanted. I suppose one of the reasons fairy tales are so easily updated, fractured, or twisted is due to their universality. Nearly every culture as a version of many fairy tales, like Cinderella or Thumbelina, so this book can appeal to many readers. Get this book for your library. Promote it to students so they can read it. Coax teachers into using if they do any sort of unit that involves fairy tales. Encourage people to take Yolen and Dotlich's advice in the introduction that says, "Why not try writing fairy-tale poems yourself? Pick a character or an object... Imagine. Enchant. Write a poem that rewrites the tale. Make a little magic" (Yolen and Dotlich 2013, 5).

*********************************************************************************

Spotlight on...

"Happily Ever After"

Imagine them all*********************************************************************************

after the plotting, after the ball,

after the spelling, hopping, sweeping,

grumping, grousing, mopping, sleeping,

from small glass shoe to nuisance pea,

so ever after, all happily be --

enchanted with magic

from kingdoms

to seas

Now close your eyes,

and dream of these.

-- Rebecca Kai Dotlich (2013, 40)

It seems a little easy to choose this poem as the gateway to an enrichment activity, but this makes twice in the book Yolen and Dotlich have exhorted their readers to use fairy tales as a springboard into creating their own poetry.

Students will be able to choose a fairy tale from any culture, and using Yolen and Dotlich's advice, choose a character, either main or background, or an object integral to the action of the poem, and write their own poem about the action before, during, or after the fairy tale. Students can use poetry forms, if they find they need a framework to get started. They can use acrostics, biopoems, found poetry, list poems, or question poems. Students can opt to do concrete poems (imagine doing one as Cinderella's shoe!) or epitaph or elegy poems. If students feel so inclined, they can use a program like Storybird to inspire or illustrate their poems. It would be fun to post students' poems (with their permission, of course!) around the school.

*********************************************************************************

Works Cited

Yolen, Jane and Rebecca Kai Dotlich. 2013. Grumbles from the Forest: Fairy-Tale Voices with a Twist. Illustrated by Matt Mahurin. Honesdale, PA: WordSong.