ISBN: 978-0-7636-4727-8 (hardcover)

|

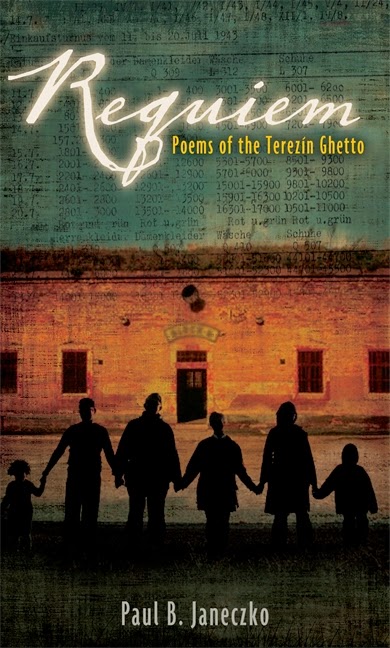

| Cover image from www.candlewick.com |

Each poem is written from the point-of-view of a different person in Theresienstadt, so we get a variety of perspectives, from young children to older adults to members of the SS running the camp. The characters, as Janeczko (2011) notes in his notes at the end of the book are largely fictional: "Some are composites based on [his] research. Others are totally invented. One exception is "Valter Eisinger/11956," a found poem taken from letters written by Eisinger, which [he] located in We Are Children Just the Same" (93). As such, each poem is titled with the name of the narrator, or in a few cases, the name of the subject of the poem. The Jewish prisoners' poems also contain their prisoner numbers. To poems are arranged in chronological order, so the first poem takes place as the Nazis began to arrest and transport Jews from their homes to the concentration camps and ghettos, and the last few poems reflect the efforts by the Nazis to liquidate the ghetto and transport its prisoners to Auschwitz and other concentration camps.

Janeczko doesn't often use a great deal of figurative language once the narrative moves into the ghetto, which seems appropriate, given the subject matter. In other works of literature I've read that depict a similar subject matter (Ruta Sepetys' Between Shades of Gray), the lack of figurative language allows the horror of the situation to become the focus of the text, rather than the language. It also demonstrates that while figurative language has a place in poetry, sometimes all the poet needs is to let the ideas, feelings, and emotions speak for themselves. Still, Janeczko uses figurative language when it would have the most impact. It's quite startling to see the liberal use of simile and metaphor to describe a family's arrest to the last poems that have little to no figurative language at all. It's as if the narrator of that particular poem has been ground down by the constant pain, hunger, and fear to the point where their mind is no longer capable of processing anything beyond its most concrete thoughts. In "Margit Zadock/13597," Janeczko uses figurative language to describe the feeling of utter shock and disbelief at the family's arrest. Margit describes her father as being "still as a lamppost / eyes locked on the nightmare / that had been his shop" (Janeczko 2011, 1). Janeczko also has Margit juxtapose an exquisite image with a more desolate one to provide an immediate contrast to illustrate the sudden change in the family's circumstance. Margit describes "Delicate handkerchiefs / now fallen white leaves" and "A white linen tablecloth... / flowed like a bride's train / from sidewalk to curb to gutter" (Janeczko 2011, 1; 2). The enormity of the situation drops on Margit and her family when they see "black boot marks / crossing [the tablecloth] like sins" (Janeczko 2011, 2). Janeczko (2011) uses metaphor to effectively evoke the image of hundreds of people moving from the trains into the ghetto in "Marie Jelinek/17789:" we joined the river of fear, / a current of shuffling feet, sobs, and whimpers (8). It's not hard to create a mental image of raging fright and simmering hysteria. In "Tomasz Kassenwitz/11850," Janeczko details the disintegration of a long friendship between Tomasz and Willi, who is not Jewish. Tomasz describes how Willi reluctantly severs their friendship, where the absence of words and movement depicts how painful this forced separation truly is. Janeczko (2011) writes, "He picked up the white king / then laid it softly on its side" (14). The act of gently positioning the king into the pose that symbolizes checkmate, a loss, is elegiac in its simplicity.

A dual-voice poem, "SS Commandant Manfred Brandt & SS Sergeant Dieter Hoffmann," uses a rhythm that conjures both the musicality of the German language and the more familiar short, abrupt patterns of the language. (Yes, spoken German can have a lyrical quality to it that is often obscured by the stereotypical harsh staccato shouts that have been seared into our collective memory.) The short phrases spoken by Hoffmann exemplify the conventional brutish sounds of German, while also voicing contempt for Brandt's methods of keeping the Jews under control. Hoffmann complains, "The Jews are playing music. / In the attics. Basements" (Janeczko 2011, 29). Brandt brings Hoffmann to see his point of view, that allowing the Jews to play music maintains an illusion that they still have a measure of control over their fates and will minimize the chance for rebellion against their captors. Brandt says,

So, let the Jews play their music, Dieter.The contrast between the rhythm of Hoffmann's staccato voice and Brandt's more lyrical one also reflects their philosophical differences. In the poem, Janeczko uses their two voices to effectively illustrate the logic employed by Kommandant Brandt to justify his actions, and to provide the questions under the voice of Sergeant Hoffmann that lead to the rationale.

In fact, we will do what we can --

within reason, of course --

to assist...

Because, Dieter, the day will come

for all of them

when there will be no more music. (Janeczko 2011, 31)

One of the best examples of using white space and line breaks to help set the tone is "Hilda Bartes." The poem is narrated from the point-of-view of a resident of the town of Terezin. As Hilda begins to describe the town, she lists what she felt were its good qualities: "Quiet. / Isolated" (Janeczko 2011, 33). The very qualities that made Terezin a good town in Hilda's estimation were also what made it an appealing location for a Jewish ghetto. Placing the terms 'quiet' and 'isolation' on separate lines allows the reader to pause to let those two words meld in order to create an image of an idyllic valley. The white space between stanzas signals a shift as the situation grows darker and more grim.

In "Josefine Rabsky/10890," Janeczko ends each stanza with the means by which a person left Theresienstadt. Most of them list the transport that took them away to a concentration camp, and their likely death. Two of the stanzas end with a death from disease or suicide. It's a powerful refrain, and the relentless mentions of the transports evokes the relentlessness of death and dying.

Even with over twenty-five separate characters, Janeczko manages to make each voice sound unique in Requiem. The irony nearly drips off the page in "SS Lieutenant Theodor Lang," who scoffs at the Red Cross inspection, but details all the 'improvements' to the ghetto so they can placate the Red Cross and the king of Denmark before he cynically remarks that, "We waited a few months / to resume the transports. / The town was getting crowded / and the ovens of Auschwitz waited" (Janeczko 2011, 58). "Nicolas Krava/21389" sets a tone of stoic resignation as it details how delightful Nicolas was in the children's opera Brundibár, but his number came up just days after his stellar performance, and they replaced him as his transport "clattered toward death" (Janeczko 2011, 69).

The poems might not be entirely relatable to children and teenagers reading them today, but they are compelling. The inclusion of poems written in the voices of the Terezin townspeople and the SS members running the ghetto means that students will gain a multi-faceted perspective of the life in Terezin. Janeczko avoids mawkishness, which is a definite skill when writing about a deeply emotional subject. The sentiment present in the poems, such as that displayed in "Wilifred Becker/34507," comes from an authentic place, as Wilifred describes how he played his violin for a married couple spending their last hours together before the husband is taken away on a transport. Janeczko also avoids using overly frilly language, letting the narrators of the poems simply describe what is happening to them. The events are terrible enough without having to rely on a great deal of figurative language.

Janeczko also uses subtle hints throughout his poetry that national or cultural origin was not enough to shield one from the machinations of the Third Reich. The narrator of "Hilda Bartes" mentions how they were commanded to leave their house in order to accommodate "the Führer's historic vision" (Janeczko 2011, 35). Wilfred, upon hearing a request to play Johann Strauss for the couple smiles, and replies, "I am German, and I not?" (Janeczko 2011, 76).

Janeczko includes several drawings from Theresienstadt prisoners: Karel Fleischmann, Ferdinand Bloch, Bedrock Fritta, and Fritz Lederer. The drawings seem to have been done in charcoal, graphite, or ink. They are striking, but they're not entirely necessary to the book. They do serve to connect the real people who were in Theresiestadt to Janeczko's fictional narrators, though. However, I feel that the book would have been just as successful if the drawings were not in the book.

There are several access features in the book. There is a table of contents, which I find helpful in verse novels or novellas, especially when you have a work with multiple characters like this. Janeczko also includes an afterword that fleshes out some of the details about Theresienstadt the poems don't cover. In the author's note, Janeczko talks about the origins of some of his narrators and some of the events he describes in the poems. He reiterates that while the Red Cross inspection actually happened and the 'improvements' as described by Lieutenant Lang were real, Lang's words are "products of [his] imagination" (Janeczko 2011, 93). Janeczko (2011) also mentions that as part of his research, he visited Terezin and the memorial and museums. Janeczko includes a list of selected sources that includes several books and websites and a couple of DVDs. He also includes a glossary of German and Czech words used in the text, translated into English.

It might make an interesting exercise to compare the poems of Janeczko with the compilation of poems and artwork by children who were in Theresienstadt called I Never Saw Another Butterfly, edited by Hana Volakova. Not only would Requiem make an excellent resource for a history or humanities class studying the Holocaust, it adds another voice for students in Judaica classes engaging in a deeper study of the Holocaust.

*********************************************************************************

Spotlight on...

"Otto Black"

The Jews are weak.

They let the soldiers push them around.

I would never permit that,

not without throwing some punches.

That I know. (Janeczko 2011, 65).

*********************************************************************************

The poetry in Requiem is often thought-provoking, make no mistake, and one poem, "Otto Beck," can help open discussion. In it, Otto declares, that he would not have allowed himself to be arrested and transported to the ghetto or a concentration camp.

When I was teaching, especially with some middle grade students, they would often make the same sort of statement as Otto. This might be an interesting poem to open a unit about the Holocaust. Once the students learn more, the class can revisit the poem and their feelings. After knowing more about the systemic violence perpetuated against the Jews in Nazi Germany, and the Warsaw Ghetto uprisings, both by the Jews and Polish Resistance fighters, would those students still feel that they could have successfully fought back, as Otto claimed?

*********************************************************************************

Works Cited

Janeczko, Paul B. 2011. Requiem: Poems of the Terezin Ghetto. Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are welcome. Please be polite and courteous to others. Abusive comments will be deleted.