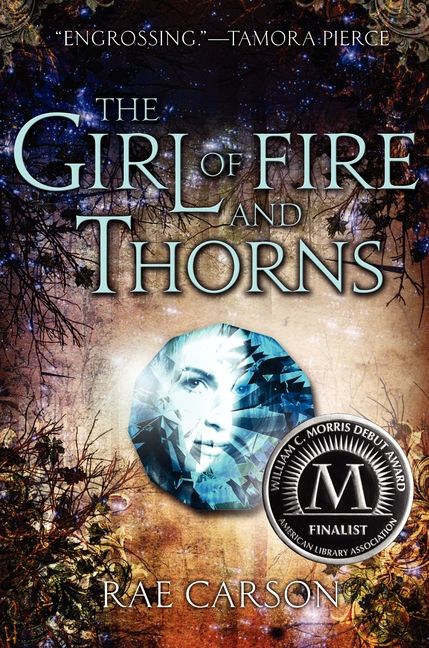

Carson, Rae. The Girl of Fire and Thorns. New York, Greenwillow Books, 2011. Print.

Lucero-Elisa de Riqueza, the younger princess of the kingdom of Orovalle, is wed in an arranged

(secret!) marriage to King Alejandro de Vega, of the neighbouring country of Joya d'Arena. Joya d'Arena is embroiled in a war with another country, Invierene, and their situation is precarious. Elisa has been marked by God with a blue gemstone (a Godstone) embedded in her navel since birth that signals she is to do somethig special. No one really knows what. Yet. Mostly because people with a Godstone tend to die while in the process of fulfilling their prophecy. Oh, and they almost always die young. All this and Elisa is only sixteen years old.

Lucero-Elisa de Riqueza, the younger princess of the kingdom of Orovalle, is wed in an arranged

(secret!) marriage to King Alejandro de Vega, of the neighbouring country of Joya d'Arena. Joya d'Arena is embroiled in a war with another country, Invierene, and their situation is precarious. Elisa has been marked by God with a blue gemstone (a Godstone) embedded in her navel since birth that signals she is to do somethig special. No one really knows what. Yet. Mostly because people with a Godstone tend to die while in the process of fulfilling their prophecy. Oh, and they almost always die young. All this and Elisa is only sixteen years old.

|

| Cover image: www.harpercollins.com |

One of the things I enjoyed the most about The Girl of Fire and Thorns was that Elisa wasn't a typical YA heroine. She's not considered particularly good-looking, much less beautiful,

and she's also quite overweight. Fat, in

Elisa's words. She uses food as a coping

mechanism until she no longer has that option and has to figure out how to deal

with any problems that arise using her own wits and intelligence. Another thing that sets this medieval-themed

fantasy novel apart is that the marriage is not something Elisa looks forward

to. She's terrified, the people in Joya

d'Arena look at her as an outsider, her husband is not the least bit interested

in her, and most people treat her like the child she still is. Carson presents a rather realistic view of what

it must have felt like to end up in a dynastic marriage.

There are lots of Spanish-language influences in the book (Carson was learning Spanish when she started writing the novel), and Elisa's religion doesn't feel as if it only resides in an alien

planet. The familiar feel of the

language and religion help ease you into the novel and quickly

establishes the setting. It think it's

important to say here that you shouldn't let the heavy presence of the world's

religion drive you away from the book.

It's absolutely integral to the

plot and Elisa as a character. Plus, Carson allows the characters to feel doubt and question their religious beliefs and faith.

The Girl of Fire and Thorns is a great action-packed read

with a relateable heroine, who repeatedly falls down, makes mistakes, and picks

herself back up (a lot!), because it's the only thing she can do.

The one thing I hated about the book was the cover. I despised it. (*gets out soapbox*) Mostly because it insisted on glamorizing Elisa and portraying her as a lithe, conventionally pretty, Caucasian girl, when she is decidedly none of those things in the novel and says so quite often. It's so glaringly wrong that the YALSA blog "The Hub" mentioned it in a post on the practice of whitewashing book covers (characters who are clearly written as people of color, but depicted as Caucasian on the cover). Face it. People judge books by their covers all the time. I'm guilty of it. But when we want teens to read for enjoyment and they want to read about people who look like they do, it must be incredibly disheartening to scan the shelves of their local library's teen/YA fiction section and only see covers with the stereotypical pretty white chick, who has hair that belongs in a shampoo commercial. (*puts soapbox away*)

The Girl of Fire and Thorns was a finalist for a William C. Morris YA Debut award in 2012.