|

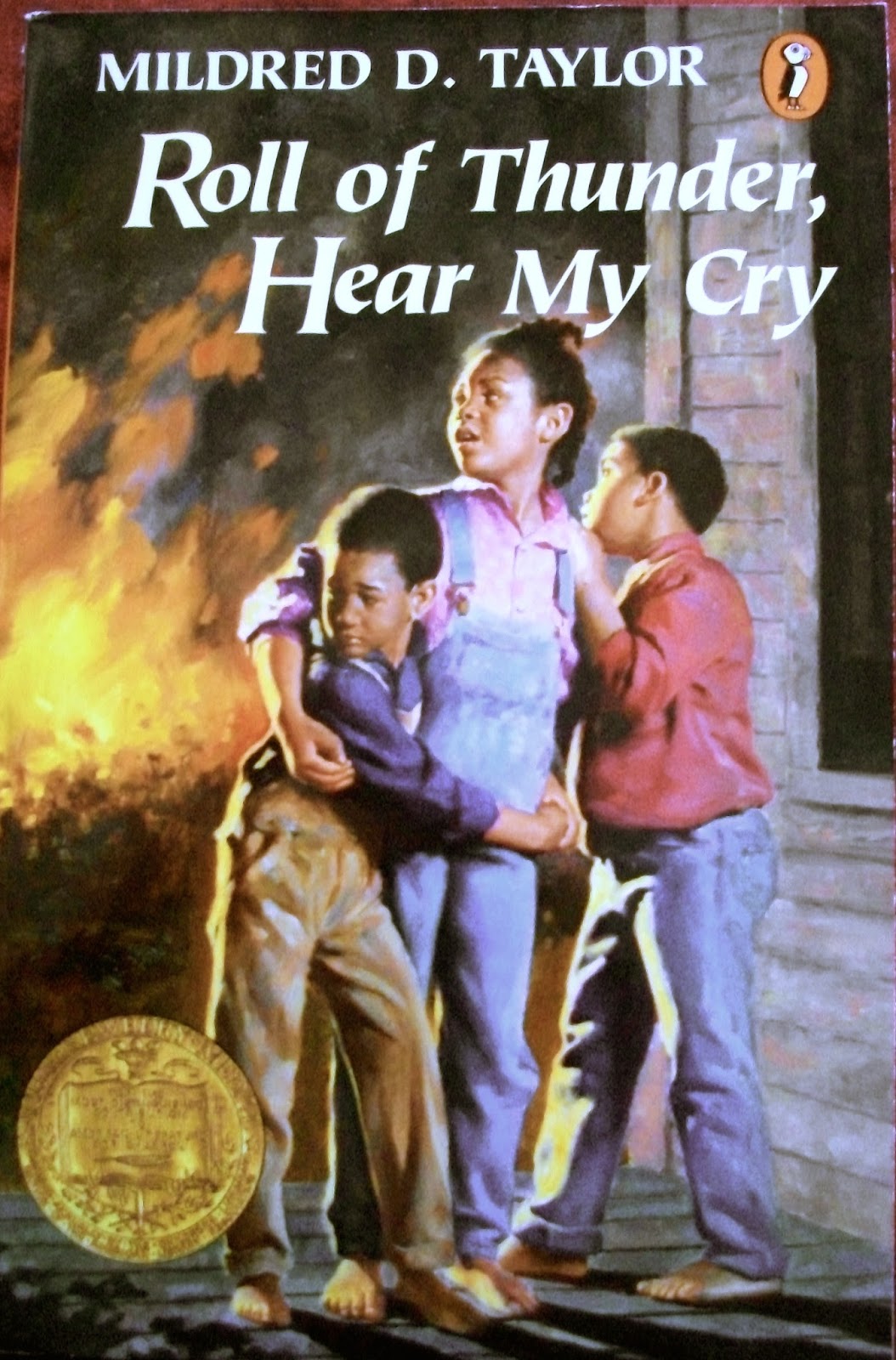

| Photo by: L. Propes |

Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry begins as the four Logan children -- Stacey, Cassie, Christopher-John, and Little Man (Clayton Chester) -- are walking to school on the first day of the term. From the beginning, Taylor uses her young protagonists to show the effects of segregation and the repressive laws and policies on African-American families in this community near Vicksburg. Each new injustice slowly unfolds until the book climaxes with the arrest and attempted hanging of Stacey's friend T.J. for the murder of a store owner in the nearby town of Strawberry. Taylor pulls no punches in showing the reader the rigidly segregated social structure. The Logan children are forced to scramble out of the way of the school bus that takes the white children to their school while the driver barrels down the dirt road in a sadistic daily game of chicken. The children in the school are given cast-off textbooks from the white school, which are not only tattered and out-of-date, but the condition of each book is noted in the front cover, along with the race of the recipient. Little Man and Cassie object to the condition of the books and the fact they have received the books only because they're no longer useful to the white school. The community is also on high alert because so-called "night riders" (most likely the KKK) recently dragged three men from their homes and set them on fire in retaliation for one of them purportedly flirting with a white woman.

The Great Depression has the Logan family and many of the other families of their community, both white and African-America, firmly in its grip. Most of the other African-American families subsist by sharecropping cotton on the farms owned by white farmers, many of whom harbor not-so-secret desires to return to the social structure of the antebellum South. The Logan family, however, owns two hundred acres of land, and are in the process of paying the mortgage on an additional two hundred acres. Unlike most of their neighbors, the Logans are not beholden to a landowner for seed, tools, or land, and consequently are somewhat better off financially. This also affords them the ability to find small ways to resist the deeply ingrained institutional racism of the community. In spite of their slight economic advantages, the Logan family must still exercise great caution when it comes to their acts of rebellion, lest they pay for it by the loss of their land.

Over the course of the novel, the reader follows Cassie as she is exposed to more and more social and institutionalized racism. Cassie and her brothers are quite isolated and "have been unusually sheltered from [racism's] stings" (Barker 124). Taylor uses Cassie as a surrogate for children who may not have experienced the struggles that the Logans have, and under the guise of Cassie's naiveté, is able to illustrate some of the harsher aspects of pre-Civil Rights era Mississippi (Barker 124). Cassie is understandably outraged by the effects of racism, and several family members attempt to persuade her to go along with it in an effort to protect her, "adding a sting of betrayal to her cruel experience" (Barker 124). As the novel reaches its conclusion, Cassie is now painfully aware of why she and other members of the community must behave just so, and "although she does not understand racism, it is presently and will be in the future a significant part of her life" (Brooks and Hampton 88).

Taylor uses other characters, most notably David Logan (Cassie's father, and based on Taylor's paternal grandfather) and T.J. as archetypes from African and African-American folk tales to deepen Cassie's understanding of the world in which she resides (Brooks and Hampton 88). Wanda Brooks and Gregory Hampton compare T.J. to "a trickster character... similar to Brer' Rabbit. His primary function... is to act as the catalyst for trouble" (88). T.J.'s myriad escapades -- from failing the previous school year to becoming involved with two much older boys from a neighboring white sharecropping family -- serve to provide the reader with a character who makes terrible and costly mistakes that demonstrate to Cassie the full force of the racism that envelops her family. David represents the hero as depicted in African folklore (Barker 128). The hero is "smaller and certainly less powerful, eventually triumph over their stronger and more powerful foes through sheer cunning and wit... they ponder, plan, and act -- sometimes quickly, sometimes deliberately -- and most often succeed in their endeavor" (Harper as qtd. in Barker 128). During the climax of the novel, David chooses to act covertly to halt the lynching of a neighbor, rather than directly confront the men.

David and his brother Hammer also foreshadow the two factions of the future Civil Rights era: nonviolent civil disobedience and those who felt equality should come by any means necessary. There are several instances in the novel where David feels compelled to physically strike back against the perpetrators of violence and/or humiliation against his family, he knows the result will likely be his death. Conversely, Hammer, who fought and was injured in World War I and now lives in Chicago where he has "a man's job and they pay [him] a man's wage for it", only reluctantly acquiesces to his brother's methods instead of meeting violence with violence (Taylor 166). The women in the novel, specifically Mary Logan, Cassie's mother and a teacher at their school, also engage in numerous acts of targeted civil disobedience, at great personal and professional risk, to confront the segregated policies that govern their lives. Jani L. Barker states, "Black readers who engage in identification with the Logans and their resistance to racism gain the benefits of seeing their culture featured positively and realistically. They see people who look like them living life authentically, with strength, love, and dignity" (128).

The overarching theme of the book centers on "experiencing, confronting, and overcoming racism" (Brooks and Hampton 89). Taylor "refuses a simple binary of black as good and white as evil. Racism itself is presented as evil, but black and white characters within the evil system demonstrate that no race has a monopoly on virtue or vice" (Barker 129). Taylor offers this perspective through T.J., whose actions often hurt members of the African-American community, and Jeremy Simms, the son of a white sharecropper who rejects his family's racist views and makes unsuccessful overtures of friendship to Stacey and the other Logan children. Taylor places this ambivalence regarding race and good and evil in a conversation between Mary and Cassie, after Cassie experiences a painfully humiliating event in Strawberry. Mary baldly states her views by telling Cassie, "White is something just like black is something. Everybody born on this earth is something and nobody, no matter what color, is better than anybody else" (Taylor 127). However, while David does not explicitly instruct his children to avoid becoming friends with Jeremy, his admonishment to Stacey to tread lightly where friendship with Jeremy is concerned also demonstrates Taylor's refusal to reduce racism to a simple black or white issue. David tells Stacey

Right now you and Jeremy might get along fine, but in a few years he'll think himself a man but you'll probably still be a boy to him. And if he feels that way, he'll turn on you in a minute... We Logans don't have much to do with white folks. You know why? 'Cause white folks mean trouble. You see black folks hanging 'round with whites, they're headed for trouble. Maybe one day whites and blacks can be real friends, but right now the country ain't built that way. Now you could be right 'bout Jeremy making a much finer friend than T.J. ever will be. The trouble is, down here in Mississippi, it costs too much to find out... So I think you'd better not try (Taylor 158).David leaves the final decision up to Stacey, but his feelings about the matter are quite clear, and in many ways, diametrically opposite of Mary's.

Personally, I found Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry to be profound and deeply thought-provoking. I had to stop reading it from time to time in order to absorb the developments of the plot. Taylor writes Cassie with equal measures of sass, wit, and wounded innocence. The rhythm of the language rolls and shifts off the characters' tongues, and subtle, but noticeable, differences in speech patterns are given to each character. Most of the character development is given to Cassie and Stacey, as they learn to navigate the world around them. The characters are clearly delineated in their personalities to help keep them separate in a reader's mind. There is a vast cast of characters that populate this novel. Keeping track of them can be a bit challenging from the sheer amount of them if a reader isn't paying attention. I also rather liked that Taylor ended the novel on an unsettled note, rather than neatly tying everything up with a bow. It would have been unrealistic otherwise.

Halfway through Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, I thought it could make for a good comparative literature unit in high school English classes to compare this novel with Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird. They are both set in the 1930s in the South (Mississippi and Alabama respectively), with young narrators attempting to understand the racist policies and philosophies that permeate and dictate how they live. They also each have an African-American character accused of a crime he did not commit, with devastating consequences. I also think it would make a fine entry into a unit of African-American history through literature, with A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry; or Fences, Joe Turner's Come and Gone, or The Piano Lesson by August Wilson for older students. Middle grades could read Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry in English classes while they study the Great Depression in history classes.

In addition to Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, Taylor wrote several other books about the Logan family, all drawn from her own family's experiences in Mississippi: Let the Circle Be Unbroken, The Land, The Road to Memphis, The Friendship, Song of the Trees, The Well, and Mississippi Bridge. She also wrote The Gold Cadillac.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Works Cited

Barker, Jani L. "Racial Identification and Audience in Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry and the Watsons Go to Birmingham—1963." Children's Literature in Education 41.2 (2010): 118-45. Web.

Brooks, Wanda, and Gregory Hampton. "Safe Discussions rather than First Hand Encounters: Adolescents Examine Racism through One Historical Fiction Text." Children's Literature in Education 36.1 (2005): 83-98. Web.

Taylor, Mildred. Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. New York: Puffin Books, 1976. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are welcome. Please be polite and courteous to others. Abusive comments will be deleted.