|

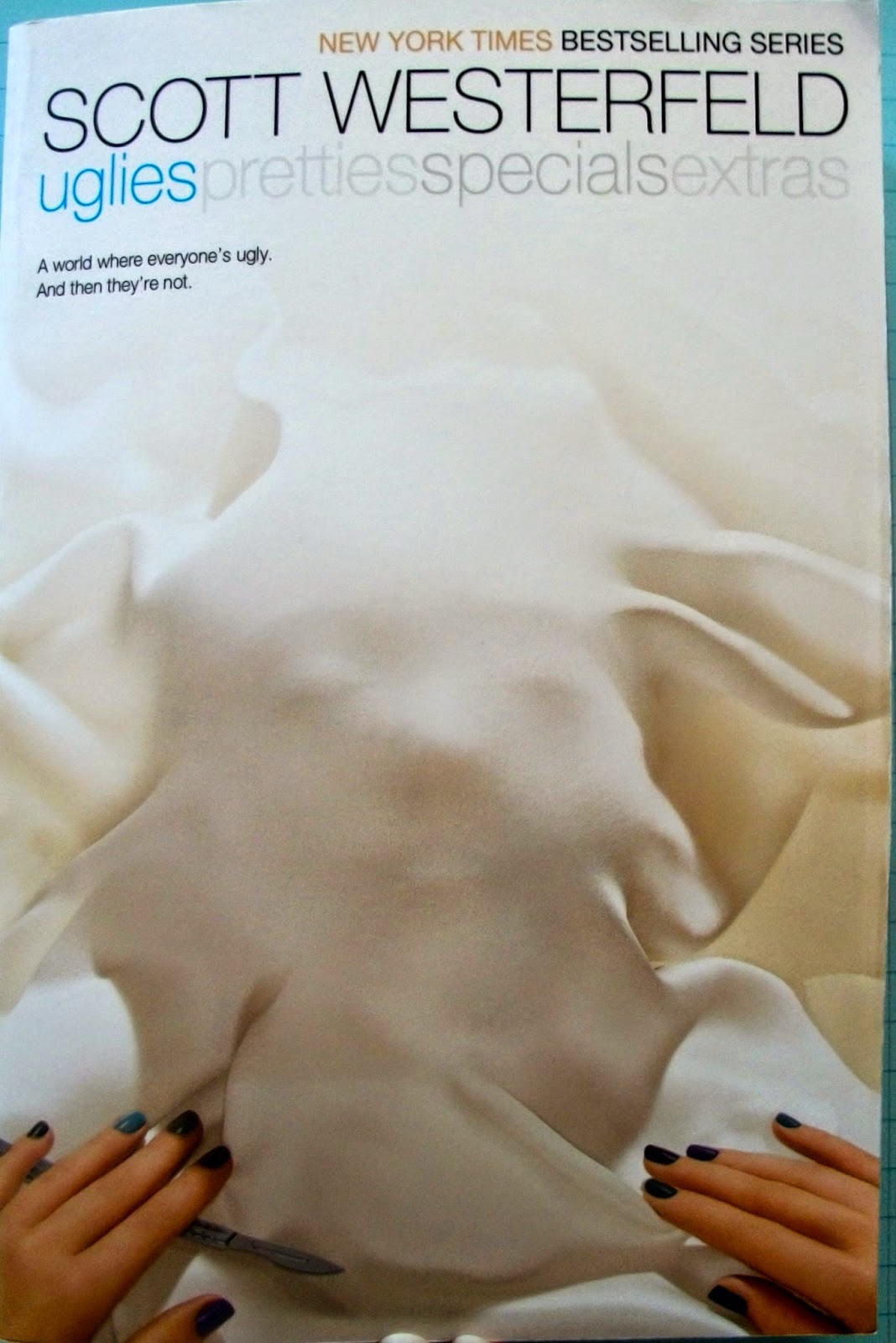

| Photo by: L. Propes |

Tally lives in Uglyville, the area of the city where all teenagers live from the age of 12 until their 16th birthday, whereupon they will be taken to the hospital and undergo a brutal surgery that will not only make them "pretty", but radically change their bodies. (The descriptions of the surgery are not for the faint of heart. It's not terribly graphic, but if watching old episodes of ER make you squeamish, you might want to skim those lines in the book.) Tally's best friend Peris had the surgery on his birthday, three months ago and now lives in New Pretty Town, a glittering community where the new Pretties live after their surgery. Tally misses Peris, and sneaks into New Pretty Town to see him. Needless to say, she isn't supposed to be there. Tally manages to leave without being caught by the authorities for being out of bounds and runs into Shay, another Ugly waiting to become Pretty. Shay is different from Tally: she is content with her looks, isn't waiting with bated breath to become a Pretty, and has plans to run away to a mystical place called the Smoke where people can choose to keep their original face and maintain control over their lives.

When Shay runs away just days before her 16th birthday, the consequences fall hard on Tally, who is brought into Special Circumstances where the sinister Dr. Cable offers her an ultimatum: find the Smoke and lead Special Circumstances to its location, or stay an Ugly forever. To Tally, who has dreamed of nothing more than becoming a Pretty, this is a fate almost worse than death. Tally manages to reach the Smoke where she discovers life in New Pretty Town isn't all it's cracked up to be.

In this novel, Westerfeld's gifts lie in the descriptions of the landscapes and the character's actions. From the beginning, with the portrayal of life in New Pretty Town signals that this isn't your run-of-the-mill dystopia. As the heroine, Tally isn't necessarily dissatisfied with her life. She never contemplates leaving the city until forced to do so by the Special Circumstances. Tally isn't going to rebel against the government initially, because to her, she has nothing about which to be rebellious. The small details of government intrusion are part and parcel of her existence. It doesn't occur to Tally to even consider the constant tracking of her person and activities might have a more ominous purpose other than safety. Nor does it occur to Tally to question the need to make all the residents of the city uniformly beautiful. At least not until she lands in the Smoke and encounters David, who was born in the Smoke and shows Tally there's another way to live life and gain satisfaction from it. Unfortunately, as a character, Tally is somewhat passive. She rarely acts on her own, unless someone forces her hand. This isn't to say she isn't intelligent. She is. Shay leaves Tally a cryptic message with directions to the Smoke that Tally successfully and easily interprets, and when presented with pieces of information, Tally can easily connect the dots and come to her own conclusions about things.

The setting in Uglies is one of the most well-done aspects of the book. It's not too terribly difficult to picture towering houses that seem lighter than air, filled with shrieking, pretty teenagers. The glimpse we see of life in New Pretty Town resembles a university fraternity straight out of Hollywood, in a never-ending cycle of fancy dress and formal parties. It's also not hard to see the remains of the Rusty Ruins or the settlement at the Smoke, due to Westerfeld's vivid descriptions.

Other ways in which the setting provides the structure for another underlying theme of the novel are the Rusty Ruins and a field of genetically modified snow-white orchids. The Rusty Ruins were once a major city, its inhabitants killed and structures left to moulder as a reminder of how ecologically destructive people used to be. The explanation is that someone created a bacteria to infect petroleum, which would then render it unstable. The petroleum (and its products) "exploded on contact with oxygen. The spores were released on the smoke, and spread on the wind" (Westerfeld 329). Society and life as the Rusties knew it was gone. The orchids were a valuable flower, whose bulbs recall the tulip mania of seventeenth century Holland. They were so valuable that someone tinkered with their genetic structure to make them adapt to various growing conditions. The result is that the orchids are now a noxious weed that chokes out any other life form turning the area into a biological wasteland.

Finally, there's the reason why the people in the city undergo such extensive plastic surgery: "A million years of evolution had made it part of the human brain. The big eyes and lips said: I'm young and vulnerable, I can't hurt you, and you want to protect me. And the rest said: I'm healthy, I won't make you sick... It was biology, they said at school. Like your heart beating, you couldn't help believing all these things, not when you saw a face like this. A pretty face" (Westerfeld 16). There are echoes of Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451 in Westerfeld's Pretty culture. In Fahrenheit 451, books are banned so as not to upset people by the ideas in them. In Uglies, "everyone is happy, because everyone looks the same: They're all pretty" (Westerfeld 254). One of the clever bits is how the government succeeds in convincing every child that they are indeed Ugly. They've been conditioned from birth to think they are ugly ducklings just waiting to become a swan when they turn 16. Furthermore, they're taught in school that "Everyone judged everyone else based on their appearance. People who were taller got better jobs, and people even voted for some politicians just because they weren't quite as ugly as everybody else... people killed one another over stuff like having different skin color... So what if people look more alike now? It's the only way to make people equal" (Westerfeld 43). The government also does something to their brains during the initial plastic surgery to make the people seem "sure of themselves... confident, and at the same time disconnected from... ugly real-life problems" (Westerfeld 258). It turns the teenagers into docile, contented people, who reinforce the status quo. Jennifer Mattson's review in School Library Journal calls it an "eerily harmonious... society" (1287).

Westerfeld has also carefully appropriated technology from films, like the hoverboards from Back to the Future II, and added his own touches, like the crash bracelets Tally wears to keep from falling to the ground if she falls off her hoverboard or bungee jackets that mimic the experience of bungee jumping, but are used as a safety device in case of a fire. Westerfeld doesn't allow the technology to overshadow the story, and it doesn't veer out of the realm of impossibility. The hoverboards use a magnetic system that utilizes the metals in the earth and water. It grounds the plot in a foreseeable future. She can even control her wall screen (think really massive computer monitor) with eye blinks.

The characterizations are somewhat stereotypical. Tally as the young adult who leaves home in search of something (Nilsen et al. 348). David, the native Smokie, has the advantage of having grown up independent of the city, yet his parents are refugees from the city. He's been taught everything Tally and Shay have, but his knowledge is heavily peppered with a dose of reality, not what the city wants him to believe. Shay is the Friend archetype, whose actions ultimately propel Tally into action (Nilsen et al. 348). David's parents, Maddy and Az, can be classified as Sages (Nilsen et al. 348). It's their story that allows the puzzle pieces to fall together in Tally's mind. The novel's main weakness to me is that the characters never quite rise above their archetypes and develop into complex characters. This could change as the series continues.

The novel weighs in at just over 400 pages, which is not an insignificant amount to some readers. Westerfeld keeps the pace up through his animated depictions of the action. The book isn't very dialog-heavy, and the pace of the book rests on the action sequences. I'd like to note here that when I say action, I don't mean it reads like an Indiana Jones movie. It's the descriptions of Tally's life, what Shay and Tally do before Shay runs away, and Tally's journey to the Smoke that make up the action that keeps the book moving along briskly. It does lag a bit in places, especially when Tally and Shay make repeated references to the selfish silliness that caused the destruction of the Rusties. Westerfeld's ecological message becomes blunted after hearing yet again how dumb the Rusties were.

One thing that is interesting in the book is that today's fashion models are not considered the epitome of beauty in Tally's age. Quite the contrary. In a poignant scene after Tally arrives at the Smoke, Shay shows her magazines from our time, full of what we consider "pretty", or rather what the media tells us is pretty. They're amazed at how thin these women are, how unhealthy they look. This scene is a pointed jab at conventional ideas of beauty and leads a reader to question if someone like Nicole Kidman would be considered unhealthily thin, just what is the city's idea of perfect beauty and proportion?

The two overarching themes of ecological damage and standards of beauty seem to be fighting one another for supremacy in the novel. Hopefully Westerfeld can link them together in the later books. Seeing as how this is the first of four novels, there's a lot of exposition in this novel that hopefully lays a good foundation for the other three.

Teachers can use Uglies one of two ways. They can use it to discuss body image and the definition of beauty and how it changes from culture to culture, and even from era to era. Teachers can also use it as part of a unit on ecology and the environment. Laura McConnell, a middle school librarian, uses the Uglies series in a display about environmental issues, pairing the books with non-fiction titles about renewable energy (School Librarian's Workshop 12).

Westerfeld's other novels include: the rest of the Uglies series -- Pretties, Specials, Extras; the Leviathan series -- Leviathan, Behemoth, and Goliath; the Midnighters series -- The Secret Hour, Touching Darkness, and Blue Noon. Uglies was also turned into a graphic novel, but presented from Shay's point-of-view called Uglies: Shay's Story.

You can visit Westerfeld's webpage. It has a schedule of his upcoming events, book trailers and discussion questions.

***********************************************

Works Cited

"Ideas on Display." School Librarian's Workshop 29.6 (2009): 12-. Education Source. Web. 27 June 2014.

Mattson, Jennifer. "Uglies (Book)." Booklist 101.14 (2005): 1287-. Education Source. Web. 27 June 2014.

Nilsen, Alleen Pace, et al. Literature for Today's Young Adults. Boston: Pearson, 2013. Print.Westerfeld, Scott. Uglies. New York: Simon Pulse, 2005. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are welcome. Please be polite and courteous to others. Abusive comments will be deleted.